Bangladesh has signed a deal with Myanmar to return hundreds of thousands of Rohingya Muslims who fled a recent army crackdown.

A statement from the Bangladesh foreign ministry said displaced people could begin to return within two months.

The two sides say they are working on the details. The crisis has been called ethnic cleansing by the UN and the US.

Aid agencies have raised concerns about the forcible return of the Rohingya unless their safety can be guaranteed.

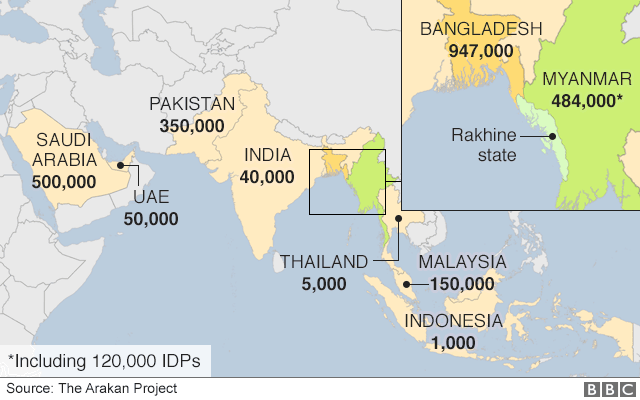

The Rohingya are a stateless minority who have long experienced persecution in Myanmar, also known as Burma.

More than 600,000 have fled to neighbouring Bangladesh since deadly Rohingya attacks on police posts prompted a military crackdown in Rakhine state in late August.

On Wednesday, US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson said Myanmar’s military action against the minority Rohingya population constituted ethnic cleansing.

- Why won’t Aung San Suu Kyi act?

- Tales of horror from Myanmar

- Who are the Rohingya group behind attacks?

“The ‘Arrangement’ stipulates that the return shall commence within two months,” a press release from the Bangladeshi government said.

Few other details were released following the signing of the memorandum in Myanmar’s capital Nay Pyi Taw.

Bangladesh Foreign Minister Mahmood Ali said it was a “first step”. Senior Myanmar official Myint Kyaing said it was ready to receive the Rohingya “as soon as possible”.

Myanmar’s conditions of return remain unclear, and many Rohingya are terrified of being sent back. Refugees at Kutupalong Camp in Bangladesh said they want guarantees of citizenship and their land returned.

“We will go back if they don’t harass us and if we can live life like the Buddhists and other ethnic minorities,” one man, Sayed Hussein, told Reuters.

“I don’t trust the Myanmar government. My husband left three times and this is my second time to leave. The Myanmar government is always like this,” a woman, Narusha, said.

Last week Myanmar’s powerful military head, Min Aung Hlaing, told Mr Tillerson that Rohingyas could return to Myanmar only if “real citizens” accepted them, referring to ethnic Rakhine members of the country’s Buddhist majority.

Both countries are under pressure on the issue, for different reasons.

Bangladesh wants to show its population that the Rohingya will not be permanent residents – it was already hosting about 400,000 before the latest influx.

The Burmese authorities – and particularly de facto leader Aung San Suu Kyi – are responding to international calls to do more to resolve the crisis.

The UN refugee agency hoped any agreement would “respect the right of refugees to return to Myanmar in a safe, voluntary, dignified and sustainable way”.

“As the UN agency mandated to assist, protect and seek solutions for refugees, we stand ready to assist in the process to ensure that returns take place in line with international standards,” a spokesperson said.

Amnesty International said it doubted there could be safe or dignified returns of Rohingya to Myanmar “while a system of apartheid remains” and added that it “hoped those who do not want to go home are not forced to do so”.

“It is completely premature to be talking about returns when hundreds of Rohingya continue to flee persecution and arrive in Bangladesh on an almost daily basis,” a spokesperson said.

“We’re also concerned that the UN… have been completely sidelined from this process. This does not bode well for ensuring a really robust voluntary repatriation agreement that meets international standards.”

Last week the Burmese army exonerated itself of blame regarding the Rohingya crisis.

It denied killing any Rohingya people, burning their villages, raping women and girls, and stealing possessions.

The assertions contradict evidence seen by BBC correspondents.

Pope Francis is due to arrive in Myanmar on 26 November. His visit will include meetings with Myanmar’s army chief and Aung San Suu Kyi, the Vatican has said.

The pontiff will later travel to the Bangladeshi capital, Dhaka, where he will meet Rohingya refugees.

Rohingya inside and outside Myanmar

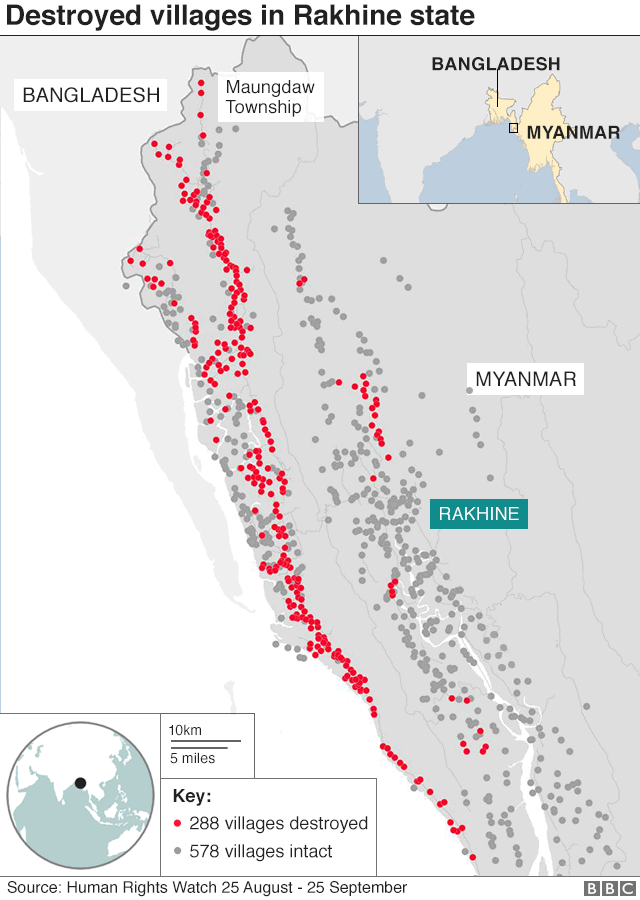

Human Rights Watch says most damage occurred in Maungdaw Township, between 25 August and 25 September – with many villages destroyed after 5 September.